About

This webpage is created to show how various Korean diasporic communities across the world have led social activities to commemorate South Korea's Sewol Ferry disaster 2014. These series of social activities also have contributed to raise public awareness on the Ferry disaster and following political, social issues in Korea.

April 16, 2014

The Sewol ferry was sank capsized, en route from Incheon to Jeju in South Korea. It carried 476 passengers, including 325 high school students who were on a field trip. During the capsizing, the crew members told passengers not to move but to stay in their rooms. While passengers stayed in the ferry as instructed, the captain and crew members abandonded the ship. As a result, only 172 people were rescued and rest of them were dead or missing. Among the 304 victims, 261 were high school students.

During the capsizing and the subsequent reporting, Korean government's announcements and rescue operations have been inconsistent and inaccurate. They could not react properly in time, their communications with families of victims were a failure as well. Consequently, heated political debates and criticism of the government started to be engendered not only in the domestic Korean society, but also among Korean diasporic communities.

Since June 2013, about a year before the Sewol ferry accident, there had had some effort to mobilize social movements through online Korean diasporic communities for denouncing election fraud and regression of democracy in Korea. The Sewol ferry disaster became the catalyst for these social movements of Korean digital diaspora. Specifically, they plan various actions on the basis of where they live and recognize that their movements may have an impact on Korean society, as well. For instance, during the turmoil of heated online discussions on various websites right after the ferry incident, one Korean-German journalist posted on a website that she had gotten a call from the Korean Embassy in Berlin. She had been told not to criticize the Korean government in her news article regarding the disaster. Her post became a huge sensation, not only in online communities in Korea, but also in overseas Korean diasporic communities. In particular, people of the Korean diaspora were upset by the Korean government’s intervention in this incident. Many of them did not hold Korean citizenship any longer, so they thought that the Korean government did not have a right to give them orders about what to do. While they started to question the Korean government’s legitimacy of overseas media censorship, the Korean diaspora also attempted to determine what they could do as overseas Koreans. From this point, the Sewol Ferry disaster, indeed, became the key event leading online diasporic communities overseas to surface in Korean society. It further made members of the Korean diaspora question and provided a motivation to reshape their own identities.

On May 2014, members of MissyUSA.com, one of the largest online community for Korean immigrant women in the U.S., initiated a fundraising campaign to publish a newspaper advertisement in the New York Times, aiming at raising awareness on the ferry disaster in the larger, non-Korean society. Within thirteen hours after their fundraising had been launched, they reached their targeted goal. Indeed, they collected about $160, 000 in only ten days. Over 4,000 people donated to the fundraising campaign. Most of the participants were Korean immigrants living in the United States, while others were also immigrants from other countries.

The first campaign in the New York Times, May 13, 2014

The advertisement they created, "Bring the truth to light," was published in the New York Times on May 13th. On that day, Korean immigrants in the United States also planned a rally to protest against the South Korean government in order to maximize the impact of the advertising. The rally was a huge success across the United States. Each protest group uploaded their rally pictures from the fifty United States.

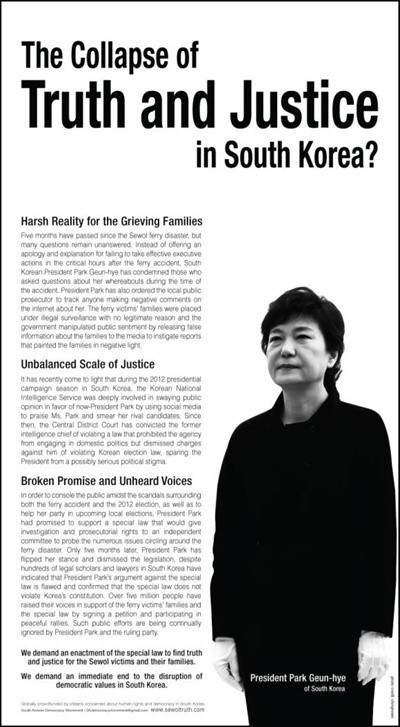

The Second campaign in the New York Times, August 17, 2014

The third campaign in the New York Times, September 24, 2014

The series of campaignes encouraged not only the Korean immigrant community but also the host country to pay attention to the ferry disaster. These series of movements helped Korean society to recognize the Korean diaspora and their online communities. At the same time, online communities for Korean immigrants recognize themselves as diasporic communities that voluntarily interact with the homeland and its people there. Gaining confidence in what they could do, online Korean diasporic communities started to design and vigorously participate in offline activities since 2014.

This webpage introduces how diverse Korean diasporic communites have planned and participated in multiple social activities. It also shows how these communities have interacted each other and enlarged their social networks globally based on the digital space.